The entertainment industry dazzles us with glamour, fame, and endless adoration. But beneath the spotlight lies a darker truth — one that Perfect Blue, a 1997 psychological thriller by Satoshi Kon, captures with disturbing accuracy. More than two decades before conversations about mental health and celebrity burnout became mainstream, Perfect Blue peeled back the glittering curtain to expose the emotional toll of a life lived for public consumption.

In doing so, it anticipated — and cautioned us against — the psychological risk run by artists well ahead of social media blew up the problem.

Stars and the Identity Crisis

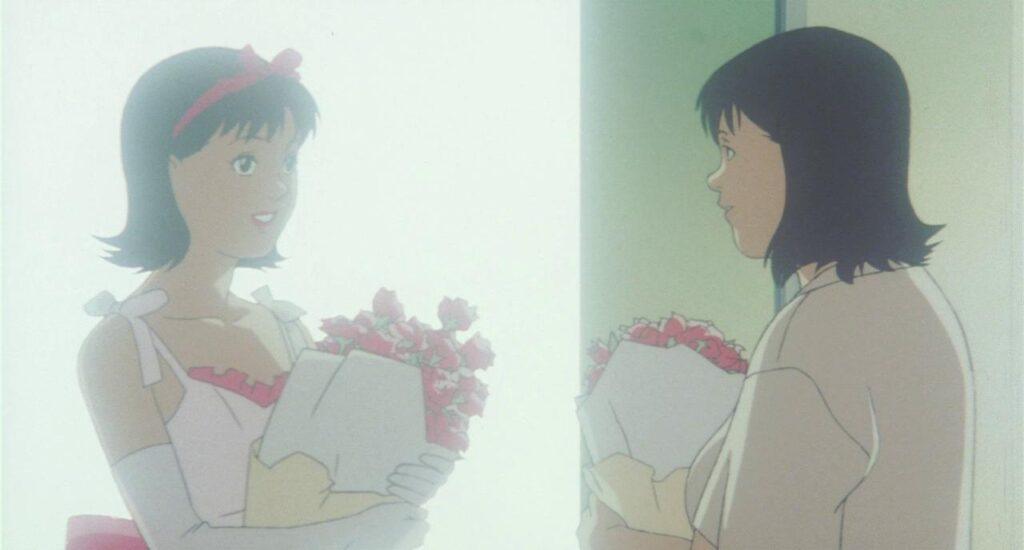

At the forefront of Perfect Blue is Mima Kirigoe, a pop idol who leaves behind her candy-coated persona to pursue acting. What is initially a professional change becomes quickly a psychological disintegration, as Mima struggles with being what she used to be, being what she is expected to be, and being what she wants to be.

This identity crisis lies at the very core of this portrayal of mental illness in film. Mima’s identity is continuously eroded — by greedy employers, corporate expectations, and even by fans. She begins doubting reality, her choices, and eventually her own sanity. This is an all too familiar issue for entertainers: time and time again, artists are asked to be anything else other than who they are.

Surveillance and Self-Policing

In Perfect Blue, Mima discovers a site called “Mima’s Room” — a fan-written diary that tracks her every step, thought, and emotion as if she wrote it herself. The nauseating aspect? It’s disturbingly accurate. The site becomes a psychological trap, and she’s confronted with a reflection of herself created by other individuals.

This foreshadowed our own age of constant watching, where celebrities — and the rest of us — are pressure to pose each move for the approval of the public. With entertainers, it is a never-ending loop of performing, even after the show stops. The stress of maintaining the charade is fertile ground for anxiety, desperation, and self-disintegration — all of which Mima endures.

Exploitation and Consent

Mima’s first big breakout as an actress is a gory, exploitative scene that she’s clearly uncomfortable with. Her agency devalues her hesitation in the interest of “career advancement,” pushing her further into battles with her own boundaries.

Perfect Blue unflinchingly brings into focus the problem of consent erosion in the entertainment industry, particularly for young women. This scene, and the trauma it causes, is an example of how entertainers have to make a choice between being successful and maintaining self-respect — a compromise that can result in long-term psychological harm, including PTSD, dissociation, and breakdowns.

The Reality of Mental Health in Showbiz

What is so visionary about Perfect Blue is the manner in which it represents mental illness — not as a kind of ghostly presence or diffuse melancholy, but as a gradual psychological collapse driven by stress, loss of control, and media harassment.

Mima’s hallucinations, paranoia, and disorientation are not overwrought; they are disturbingly real manifestations of an individual going completely crazy. Today’s talk of celebrity burnout — from K-pop idols taking mental health vacations to Hollywood celebrities ditching social media — echoes a lot like Mima’s experience back in the late ’90s. Perfect Blue was one of the first anime movies to show how fame doesn’t only steal your time — it can steal your mind too.

What Perfect Blue Got Right — and Why It Still Matters

Perfection Blue remains pertinent because it spoke the truth before the world was ready to hear it:

– Mental illness in the entertainment world is routinely overlooked until it’s too late.

– Women artists are constantly objectified, manipulated, and stripped of agency.

– Public personas may consume private identities.

– Obsession and parasocial relationships are not compliments — they are dangerous.

In an era of internet fandoms, constant connection, and social media stress, Mima’s story speaks to us more than ever. Her collapse is a warning — not just for performers, but for us, the audiences of their work. When we commodify performers without seeing their humanity, we perpetuate the system that wrecks them.

Final Thoughts

Mental illness in entertainment isn’t just a secondary topic — it’s an epidemic. Perfect Blue knew that. It captured the silent agony behind fame and exposed the chilling cost of existing under a microscope, being judged, and constantly redefined.

No matter if you’re a fan, a creator, or simply a person attempting to grasp the toll of fame, Perfect Blue is not just an anime — it’s a psychological bombshell of truth. And it still loudly resonates clear today.